Over the weekend, I was inspired by supervising our high school “STEMX” Global Citizenship in Action team as they hosted an exceptional “AI in Science Day” for middle school students from across Beijing. From ideation to planning and hosting the entire day, this team of caring, motivated young people put together an engaging and hands-on experience for a diverse range of learners, with the focus of AI and Medicine. They researched, planned, worked with leadership, tech and facilities, secured a keynote, learned new tools (such as Raspbot AI cars) and delivered a fantastic 8-hour day of exhausting, exciting learning. They introduced complex ideas and made them accessible, iterated on their workshops in the moment and got to the end of the day with plenty to be proud of. I’m proud of them.

It made me reflect on the skills and dispositions that students will need to flourish as they move forwards, and reminded me of a post from 2017, on the TEMPERed Learner. Inspired by Cultures of Thinking, the IBATL, Bold Moves for Schools and The Quest for Learning, I was about to move to a school that was really focused on the futures of learning. In the 8 ½ years since, my learning has grown, from EdD research and my role, and the world of international education is making some big shifts: agency, flourishing, complex competencies, a pandemic and, of course, AI. New skills are rising and others remain timeless and durable. We know more about motivation, learning and empowering authentic learning.

So here’s a redux and update of the TEMPERed Learner, with old ideas, new research and some reflections. I hope you like it.

AI Transparency statement: this post pulls together 15 years of posts, research and work. As I drew from different pieces it ballooned and so I used Claude’s help to streamline some sections, give some more consistency, proof-read and sort some of the reference formatting.

Introducing The TEMPERed Learner

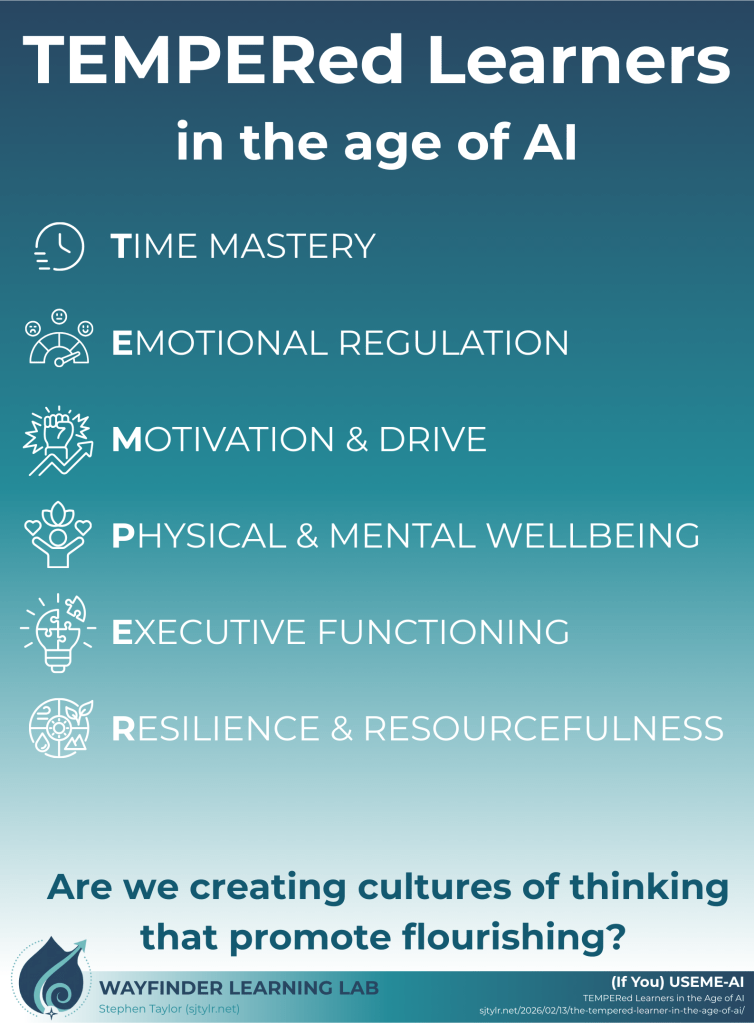

In 2017, I proposed the TEMPERed learner as an intellectual toy for the self-regulating, agentic student: the kind of graduate our schools should be producing. The acronym has six dimensions::

- Time Mastery

- Emotional Regulation and Affect

- Motivation and Drive

- Physical and Mental Wellbeing

- Executive Functioning

- Resilience and Resourcefulness.

I chose “TEMPERed” for its dual meaning: the state of mind between anger and calm, and the metallurgical process of heating and cooling metal to achieve the right balance between hardness and flexibility. The TEMPERed learner is strong enough to withstand pressure, flexible enough to adapt. You could also think of TEMPERed chocolate and how the patient, intentional process gives it its “shine”.

These dispositions do not develop in a vacuum, they grow within cultures. Ritchhart’s (2015) research on cultures of thinking identifies eight cultural forces (expectations, language, time, modelling, opportunities, routines, interactions, and environment) that shape the thinking and learning dispositions of a healthy learning community. The TEMPERed learner is not produced by a programme bolted onto the timetable, they emerge from a culture that values thinking, models self-regulation, and makes learning visible. John Hattie’s Visible Learning: The Sequel (2023), synthesising over 2,100 meta-analyses drawn from more than 130,000 studies involving 400 million students, reinforces this: what matters most is not the intervention but the teacher’s mindframe, the collective efficacy of the teaching team (d = 1.34), and the intentional alignment between learning intentions, success criteria, and teaching strategies.

The model was developed before generative AI became infused into our students’ lives. In this post, I unpack the theoretical foundations of each TEMPER dimension, connect them to the growing movement for complex competency development in international education, map them against industry demands for 2030 and beyond, and offer some cliches and suggestions for educators moving forwards.

The TEMPERed Learner in 2026

TEMPER represents a model of self-regulation that positions the learner as a whole person (cognitive, affective, physical, and social) operating within a culture of thinking that either supports or undermines their development. Each dimension interacts with the others: a student who cannot manage their emotions (E) will struggle with executive functioning (E); a student who lacks physical wellbeing (P) will find it harder to sustain motivation (M); a student without resilience (R) will collapse when time pressures mount (T).

Through some of my EdD studies, I’ve found connections I didn’t know in 2017: Zimmerman’s (2000, 2002) cyclical model of self-regulated learning, with its three phases of forethought, performance, and self-reflection; Bandura’s (2001) social cognitive theory of human agency and its four properties of intentionality, forethought, self-reactiveness, and self-reflectiveness; and, Deci and Ryan’s (1985, 2000) Self-Determination Theory, particularly the three basic psychological needs of autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Hattie’s (2023) MetaX database supports the notion that self-regulation strategies, metacognitive programmes, and formative evaluation all have effect sizes well above the 0.4 “hinge point” that represents a year’s growth per year of schooling.

So what do these elements look like in 2026?

T: Time Mastery

Mastery of time is more than basic time management; as Howard Gardner notes, “people around the world place a special premium on ‘time well spent’.” (2013). Ritchhart’s force of Time in Creating Cultures of Thinking means a resource to be invested, to preserve for thinking and something which, in how we invest it, is a statement of our values. Management implies compliance: doing what you’re told, when you’re told. Mastery arises from agency: making purposeful choices about how you invest time as a statement of your learning values. This distinction matters when AI can do a five-hour task in five minutes, disrupting how students relate to time and effort.

Additionally, Pintrich’s (2000) framework identifies time and study environment management as a key regulatory strategy associated with higher achievement. Claessens, van Eerde, Rutte and Roe’s (2007) review found that time management behaviours relate positively to perceived control and negatively to stress, while Macan, Shahani, Dipboye and Phillips’s (1990) study demonstrated that perceived control of time was a stronger predictor of outcomes than specific techniques, supporting the mastery framing. Think about how you feel when time is racing past in a state of Flow (Csikszentmihalyi, 2002).

In the presence of AI, time mastery takes on a new dimension. When AI generates a first draft instantly, the TEMPERed learner must decide: is the thinking worth the time? Fan et al.’s (2024) research on “metacognitive laziness” demonstrates that AI tools reduce engagement in self-regulated learning processes like reflection and self-evaluation, but it’s not quite that simple (more later).. The TEMPERed learner who has mastered time understands that some cognitive work is worth doing slowly, because the productive struggle is where the learning happens.

E: Emotions and Affect

Learning is emotional. Immordino-Yang and Damasio’s (2007) neuroscientific research established that emotion and cognition are neurologically inseparable: “we feel, therefore we learn.” Pekrun’s (2006) control-value theory provides a framework for understanding how emotions like enjoyment, hope, anxiety, and boredom relate to academic engagement. Positive activating emotions generally promote deep learning; negative deactivating emotions undermine it. Learning to navigate this is crucial.

Emotional self-regulation, the ability to monitor, evaluate, and modify one’s emotional reactions (Gross, 2015), is essential for sustained engagement with challenging learning. Brackett, Rivers and Salovey’s (2011) RULER framework demonstrates that explicitly teaching emotional skills improves academic outcomes, classroom climate, and student wellbeing. The TEMPERed learner can recognise when frustration is a productive signal to try a different approach, rather than a reason to give up or outsource thinking.

M: Motivation and Drive

Motivation is the engine of the model. Deci and Ryan’s (2000, 2017) Self-Determination Theory distinguishes between autonomous motivation (acting from integrated values and genuine interest) and controlled motivation (acting from external pressure). The TEMPERed learner is autonomously motivated: they engage because it matters, not merely because it is assessed. Deci and Ryan’s (2020) review confirms that autonomous motivation predicts better learning, greater persistence, and higher wellbeing across educational levels and cultures.

This matters when AI has the potential to do the assessed work on behalf of the learner. If a student’s primary motivation is the grade, AI offers a conveniently tempting shortcut, but if their motivation is understanding, the shortcut loses its appeal. Niemiec and Ryan (2009) demonstrated that teacher support for autonomy, competence, and relatedness facilitated autonomous self-regulation, supporting the argument that motivation is a condition to be cultivated through the culture of the classroom. Here the cultural forces of expectations and interactions play a crucial role: when the culture signals that learning is for understanding, not for compliance, students internalise that message.

When we talk about motivation and drive, we are really talking about effective learner agency. I’ve written plenty on that here before (and there is more to come), but with agency as the goal of learning, protecting human agency as the central tenet of AI policy guidance and the increasingly agentic nature of AI pulling for our attention, this is a real space of challenge and change.

P: Physical and Mental Wellbeing

The TEMPERed learner is flourishing: within themself, their community and the environment. In a world that seems more stressful and uncertain, this must be a key driver of healthy schools and academic achievement. Shonkoff and Phillips’s (2000) From Neurons to Neighborhoods established that physical health, emotional security, and cognitive development are deeply intertwined. Visible Learning: The Sequel emphasises that student wellbeing is a prerequisite for, not a consequence of, academic achievement.

The age of AI adds new wellbeing challenges. Twenge et al.’s (2018) research links increased screen time to declining adolescent mental health. Always-available chatbots risk displacing human connection, and the cognitive demands of navigating AI tools impose what Brod (1984) and Tarafdar et al. (2007) call technostress. AI could be used in a range of ways to support learner wellbeing, through coaching, time management and relevant feedback, but these require sustained, purposeful professional learning and awareness. The TEMPERed learner has the awareness and strategies to protect their own wellbeing in a technology-saturated environment. There is so much scope for further research in this field, and as we see the rise of importance of social-emotional learning (SEL) in international schools, I predict broader, deeper and more balanced perspectives (and actionable urgencies) will emerge. .

E: Executive Functioning

Executive functions (planning, working memory, inhibitory control, cognitive flexibility) are the operational machinery of self-regulation. Diamond’s (2013) comprehensive review identifies three core executive functions, with higher-order reasoning and problem-solving built upon them. Blair and Razza (2007) demonstrated that executive function skills are stronger predictors of early academic success than IQ.

Generative AI presents a paradox for executive functioning: it can scaffold executive processes, helping students plan and organise their thinking, but it also risks what Gerlich (2025) identifies as cognitive offloading: delegating cognitive tasks in ways that reduce executive engagement. Gerlich found a strong negative correlation (r = -0.75) between cognitive offloading and critical thinking. Tankelevitch et al.’s (2024) research highlights that effective AI use actually requires strong executive functioning: monitoring, evaluating, and adapting cognitive strategies in real time. The TEMPERed learner does not just use AI; they regulate their use of AI and, more importantly, they recognise the power of their own thinking.

R: Resilience and Resourcefulness

Resilience, the capacity to adapt positively in the face of adversity, completes the model. Masten’s (2001) “ordinary magic” framework positions resilience not as an exceptional trait but as the product of basic human adaptational systems. Yeager and Dweck’s (2012) research demonstrates that students’ implicit theories about whether intelligence is fixed or malleable significantly affect their resilience in the face of challenge.

Resourcefulness adds a practical dimension: the TEMPERed learner actively seeks solutions in the face of challenge. In the age of AI, resourcefulness includes knowing when and how to use AI, when to seek human help, and when to sit with uncertainty and think. The OECD’s (2019) Learning Compass 2030 positions this combination, which they term “student agency,” at the centre of education’s purpose.

TEMPER and the Rise of Complex Competencies

TEMPER connects to one of the most significant shifts in international education: the growing movement to assess and credential complex competencies; capabilities that go beyond subject-domain knowledge to encompass the dispositions, skills, and behaviours that define a well-rounded person. Over the last couple of years, I’ve been fortunate to engage with CIS schools in the move towards this pathway, and we have joined the CIS New Metrics for International Schools project with the University of Melbourne. Connections between this work and the IB’s Approaches to Teaching and Learning are strong, and the groundswell is building. I feel optimistic that this work can lead to effective change in how we measure and promote what we value.

Professor Sandra Milligan’s work at New Metrics is leading this shift: working with over 40 schools in Australia and internationally, Milligan’s team has developed validated assessment frameworks for seven complex competencies:

- Agency in Learning

- Collaboration

- Communication

- Acting Ethically

- Quality Thinking

- Active Citizenship

- Personal Development.

With each competency comprising an inter-related network of “elements”, their approach positions teachers who deeply know their learners as best placed to make professional judgements based on behavioural indicators of typical behaviour (Milligan, 2020). See a sample for Agency in Learning here. I am very excited about the collaboration between NM and CIS towards the competency of Socially Responsible Leadership, and am looking forward to how it can help refine our own Profiles of WAB Alumni domains and competencies.

My own confirmation bias shows alignment between these competencies and the elements of TEMPER. Agency in Learning, the learner’s capacity to set goals, monitor progress, and take responsibility for their own learning, maps directly onto Time mastery, Motivation, and Executive functioning. Personal Development encompasses emotional regulation, wellbeing, and resilience: the E, P, and R dimensions. Quality Thinking connects to the metacognitive awareness and overlays all six TEMPER dimensions.

Milligan’s team has worked hard to address the measurement challenge that has historically undermined competency-based approaches. As she notes, “traditional metrics report what a learner knows about a particular subject, or what they can do under timed, high-stakes tests,” (2020), but they fail to capture the competencies that predict thriving. This resonates with Hattie’s (2023) argument that the “grammar of schooling,” with its reliance on summative testing and content coverage, must give way to approaches that make learning growth visible across a broader range of outcomes.

If AI can replicate knowledge-recall performance on traditional assessments, those assessments lose their discriminatory power. Complex competencies are what AI cannot (easily, yet) replicate or shortcut: they develop through sustained, embodied, social practice. Bill Lucas’s (2021) work on creative thinking assessment, Claxton’s (2002) “building learning power,” and the OECD’s PISA Creative Thinking assessment all reinforce this trajectory. In past posts I’ve used Child and Shaw’s (2023) competency construct claims framework which offers a practical validation lens: What is the competency? Who is it for? How should it be used? And what difference should it make? Combining this with Cultural Historical Activity Theory (CHAT), we can interrogate how the new mediating tool of competencies might influence the activity system of the school as it shapes new rules, influences the community and division of labour and makes the shift to a new object: learner agency.

The Alignment with Industry Intelligence

Industry research suggests that TEMPER can have both educational and economic utility. The WEF’s Future of Jobs Report 2025, identifies the “rising” core skills for 2030: analytical thinking (essential for 70% of companies), resilience, flexibility and agility, leadership and social influence, creative thinking, and motivation and self-awareness. The fastest-growing skills include AI and big data alongside the human skills of curiosity and lifelong learning. There is no either-or, not anymore. Any number of equivalent studies, including the OECD’s Skills for the Future of Work (2025), find similar outcomes, as do our own discussions with experts across professions. Resilience, flexibility and agility map to TEMPER’s “R”. These data highlight a dual effect: the same forces that create jobs also displace them. As AI and economic shifts threaten previously-secure pathways, the ability to adapt, be resilient and keep on learning are essential.

Source: WEF, 2025.

(Some Of) The Challenges of AI

What if the very tools that should be used to augment learning are contributing factors in undermining the capacities our learners most need?

Fan et al.’s (2024) study found that while AI tools improved immediate task performance, they can reduce engagement in self-regulated learning processes (reflection, self-evaluation, strategic planning) leading to “metacognitive laziness.” Gerlich’s (2025) research found that delegating cognitive tasks to AI correlated strongly with reduced critical thinking, with younger users most affected, while Bastani et al.’s (2024) study concluded that generative AI “can harm learning” by creating dependency patterns. Jose et al.’s (2025) review frames this as a “cognitive paradox”: AI enhances immediate performance while eroding the processes (active recall, effortful processing, critical scrutiny) that build lasting knowledge. However, proper uses of AI can have positive effects: Kestin et al (2025) found that well-used AI tutors can outperform in-class learning with the “just right” interventions and challenges to thinking at the right time, while Suriano et al (2025) found that student interaction with ChatGPT could promote critical thinking skills under the right conditions of knowledge and engagement. Recent research from the Arts Council of England suggests promising results of human-AI co-creation and creative thinking (2025).

Whatever your view on AI, there is evidence emerging to support your opinion. Personally, I’m neither pro- nor anti-AI, but I recognise the importance of being a pragmatic idealist in the current state. It’s here, it’s growing and we need to deal with it. Students with strong self-regulation are likely better equipped to use AI strategically rather than dependently.

Tankelevitch et al.’s (2024) CHI paper demonstrates that effective AI use requires sophisticated metacognitive monitoring and control: knowing what you know, recognising when output is wrong, making strategic decisions about when to offload and when to engage are all executive functions. Xu et al.’s (2025) quasi-experimental study provides a way forward: explicit metacognitive support in generative AI environments improved self-regulated learning, reduced cognitive load, and increased academic performance. As Hardman (2025) summarises: “generic GenAI tools do not just fail to advance human learning; they often actively hinder it” unless learners bring strong metacognitive skills to the interaction.

So What Can We Do About This?

I think there is a lot that is still in our power, and it comes down to intention, purpose and reflexive practice. Plural futures of flourishing are still possible, if we make the conscious choice to take intentional paths. These recommendations are nothing earth-shattering, and anyone who knows me will have heard it ad-naseum. But I believe it, so here goes:

- Name it & claim it: Make TEMPER explicit.

Whatever you call it (TEMPER or something else), students won’t easily develop self-regulation if it remains invisible. So make it a visible, named, valued and shared language of learning. Ritchhart’s (2015) cultural forces, especially language, modelling, and expectations, create the conditions where talking about time mastery, emotional regulation, and metacognition becomes as normal as talking about subject content. Zimmerman’s (2002) research confirms that self-regulation can be taught, but it requires explicit instruction, modelling, and practice. Pull back the curtain of teaching and learning processes, making explicit to students where they’re going, how to get there and how to develop the academic and enduring skills to flourish.

2. Measure what we value: Explore complex competency frameworks.

As much as it can frustrate us, what we assess sends a strong community signal about what we value. So consider going deeper on your own research for contextually-appropriate complex competencies. A recent report from UNESCO asks us to reconsider what is worth measuring in this AI age (2025). Consider joining the New Metrics for International Schools, or piloting models such as the Mastery Learning Record, Global Citizen Diploma or Global Impact Diploma. Make explicit connections between the ATL skills and success in your disciplinary and interdisciplinary subjects. Champion this in your community.

3. Teach metacognition: before, during, and after AI use.

Scaffold the metacognitive processes that effective use demands. Require students to plan before prompting, evaluate outputs critically, and reflect on what they learned from the interaction. Xu et al.’s (2025) research demonstrates the effectiveness of this approach. Use Visible Thinking routines, framed on the thinking moves students need to make, following up with “What makes you say that?”, as structures for critical evaluation of AI output. The question is never “Is this a good answer?” but “How do I know?” I have a Thinking Routines Bot on Poe here, if you want to try.

4. Protect the productive struggle.

Bjork and Bjork’s (2011) research on “desirable difficulties” demonstrates that conditions making learning harder in the short term (spacing, interleaving, retrieval practice) produce stronger long-term retention and transfer. AI eliminates most desirable difficulties. Educators must intentionally preserve cognitive challenge: handwritten first drafts, no-device discussion, thinking-intensive problems where the process matters more than the product. Most eductors will be familiar with Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development as the sweet-spot for learning: let’s aim to stay there.

One of the most powerful things I’ve learned from Ron Ritchhart, which is now a personal and planning mantra, is to constantly ask: “Who is doing the thinking here?”

5. Design for holistic development.

Schools are often strong on executive functioning (study skills programmes) and sometimes motivation (goal-setting workshops), but they may be weaker on emotions, physical wellbeing, and resilience, though I can see this growing across our sector. Seligman’s (2011) PERMA model and the CASEL framework are examples of frameworks for embedding wellbeing into school culture. Brackett’s RULER programme demonstrates that emotional skills can be systematically developed. Value SEL as not just a standalone set of disconnected units, but as a daily opportunity to notice, name and nudge learners towards resilience and resourcefulness.

6. Authentic, real-world connections… by design.

Stay connected with industry intelligence, not as the “only goal” of learning and schooling, but as a “credibility crutch” if you need to reassure community members of the importance of this work. You could discuss the paradox: the tools that do the work for you may prevent you from developing the capacities employers value most. Frameworks such as the SDGs frame authentic contexts where agency, resilience, and ethical thinking are concrete requirements. As Ojala (2012, 2016) demonstrates, constructive hope emerges when students see themselves as capable agents within real-world challenges. I found Grant Wiggins’ (2014) work on authenticity in learning an inspiration that I frequently return to.

7. Build cultures of thinking, not cultures of compliance.

The AI “problem” is not a technology problem: it is a challenge to culture. Technology will keep changing and policy will keep shifting but culture is protective. Ritchhart’s eight cultural forces are the infrastructure within which TEMPERed learners develop. Hattie’s Visible Learning: The Sequel (2023) puts it clearly: collective teacher efficacy (d = 1.34 in the MetaX database) remains among the most powerful influences on student achievement, and it is built through shared pedagogical inquiry, not through mandated programmes. Schools that create cultures of thinking will absorb disruption far more effectively than schools that rely on compliance and control. Culture precedes technology, absorbs disruption and is how we can collaboratively TEMPER our learners. If you do nothing else with this article than read one book, please read Creating Cultures of Thinking. Then read another book, Cultures of Thinking in Action.

8. Use technology so well that we use it less… and then get outside and read a book.

One of the saddest things to see in a tech-rich school is classrooms-full of students on laptops, all day long. At worst, they become $1,000 form-filling machines, as students generate text to complete tasks to meet the demands of rubrics and then forget about any learning that happened. At best, students know when and how to use their tech to empower their learning, spending more time on interactive, interpersonal processes, deep learning, powerful thinking and authentic inquiry. We need to make it easier to do better things; to make the most powerful learning our default setting by removing barriers to giving it a go.

Students crave connection with themselves, each other, their teachers, communities and nature. If there is something I’d add to TEMPER on reflection, it would be these connections, particularly post-pandemic. I’ve long been inspired by John Dewey’s notion of experience as a moving force, something that drives learners to reflect on their experience and which in turn drives deeper learning.

So please: find those moments to build connection, create authentic learning and consider your own role as part of an extensive community ecosystem that supports truly student-centred, experiential learning. Make transfer between contexts a goal of learning, notice and name opportunities to demonstrate skills. And build in more time for really reading.

The Buoyant Force: Learning for Hope and Agency

Where can we go from here? Inspired by Bente Elkjaer’s pragmatic views on Dewey’s work (2018), the tagline on the Wayfinder Learning Lab has always been “learning is about living, and as such is lifelong.” I don’t think there are many/any really new ideas in this post; it’s a convergence of theories, practices and positions on learning. As much as I’d like trad/prog edu-binaries to disappear, it seems like they won’t, yet there is more in common between camps than people may realise. Self-regulation, emotional intelligence, resilience, and intrinsic motivation have been valued by educators for as long as there have been schools.

What might be new is the urgency. Generative AI has altered the relationship between knowledge, cognition, effort, and assessment. The skills that AI threatens to atrophy (metacognition, critical evaluation, effortful processing, persistence) are the skills the 2030 workforce demands. The complex competencies that Melbourne Metrics and others are developing assessment frameworks for (agency, collaboration, ethical action, quality thinking) are the competencies AI cannot (yet) replicate.

So TEMPER is really a call to take the whole learner seriously, including academic achievements, “AI literacies” and whatever else seems important… powered by their capacity to regulate their own time, emotions, motivation, health, thinking and response to adversity. We can help shape effectively agentic young learners on their journey to mastery and flourishing.

Time and childhood are non-renewable resources. The Spark, that visible excitement of deep understanding clicking into place, is unlikely to come from a chatbot. It comes from the hard, messy, human work of learning. Through creating a buoyant force of learning: a motivating, challenging and fulfilling journey to adulthood that values their steps and competencies along the way, we can protect the conditions for The Spark. We can choose to educate for hope, not despair in a world that seems too fast to process, to TEMPER our learners for the world they will inherit, and to ensure that in our rush to adapt to artificial intelligence, we do not abandon the cultivation of human intelligence.

References

- Arts Council of England. (2025). AI Technologies and Emerging Forms of Creative Practice.https://www.artscouncil.org.uk/ai-technologies-and-emerging-forms-creative-practice [Accessed 5 February 2026].

- Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 1–26.

- Bastani, H., Bastani, O., Sungu, A., Ge, H., Kabakcı, O., & Mariman, R. (2024). Generative AI can harm learning. Available at SSRN 4895486.

- Bjork, E. L., & Bjork, R. A. (2011). Making things hard on yourself, but in a good way: Creating desirable difficulties to enhance learning. In M. A. Gernsbacher et al. (Eds.), Psychology and the Real World (pp. 56–64). Worth Publishers.

- Blair, C., & Razza, R. P. (2007). Relating effortful control, executive function, and false belief understanding to emerging math and literacy ability. Child Development, 78(2), 647–663.

- Brackett, M. A., Rivers, S. E., & Salovey, P. (2011). Emotional intelligence: Implications for personal, social, academic, and workplace success. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 5(1), 88–103.

- Brod, C. (1984). Technostress: The Human Cost of the Computer Revolution. Addison-Wesley.

- Child, S., & Shaw, S. (2023). A conceptual approach to validating competence frameworks. Research Matters, 35. Cambridge Assessment.

- Claessens, B. J. C., van Eerde, W., Rutte, C. G., & Roe, R. A. (2007). A review of the time management literature. Personnel Review, 36(2), 255–276.

- Claxton, G. (2002). Building Learning Power. TLO.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2002). Flow: The Psychology of Happiness. Penguin.

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior. Plenum.

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268.

- Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and Education. ISBN: 0-684-83828-1.

- Diamond, A. (2013). Executive functions. Annual Review of Psychology, 64, 135–168.

- Elkjaer, B. in Illeris, K. (2018). Contemporary Theories of Learning: Learning Theorists … In Their Own Words. Chapter 5: Pragmatism: Learning as creative imagination. Routledge.

- Fan, Y., Tang, L., Le, H., Shen, K., Tan, S., Zhao, Y., Li, X., & Gašević, D. (2024). Beware of metacognitive laziness: Effects of generative AI on learning motivation, processes, and performance. British Journal of Educational Technology, 56(2), 489–530.

- Gardner, H. (2013). Health, Happiness, And Time Well Spent. WBUR Cognoscenti. https://www.wbur.org/cognoscenti/2013/02/22/time-well-spent-howard-gardner

- Gerlich, M. (2025). AI tools in society: Impacts on cognitive offloading and the future of critical thinking. Societies, 15(1), 6.

- Gross, J. J. (2015). Emotion regulation: Current status and future prospects. Psychological Inquiry, 26(1), 1–26.

- Hardman, P. (2025). The impact of Gen AI on human learning: A research summary. Substack.

- Hattie, J. (2023). Visible Learning: The Sequel. A Synthesis of Over 2,100 Meta-Analyses Relating to Achievement. Routledge.

- Immordino-Yang, M. H., & Damasio, A. (2007). We feel, therefore we learn. Mind, Brain, and Education, 1(1), 3–10.

- Jose, B., Cherian, J., Verghis, A. M., Varghise, S., & Joseph, S. (2025). The cognitive paradox of AI in education. Frontiers in Psychology, 16, 1550621.

- Kestin, G., Miller, K., Klales, A., Milbourne, T. and Ponti, G., 2025. AI tutoring outperforms in-class active learning: an RCT introducing a novel research-based design in an authentic educational setting. Scientific Reports [Online], 15(1), p.17458. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97652-6

- Lucas, B. (2021). Rethinking Assessment in Education: The Case for Change. University of Winchester.

- Macan, T. H., Shahani, C., Dipboye, R. L., & Phillips, A. P. (1990). College students’ time management. Journal of Educational Psychology, 82(4), 760–768.

- Masten, A. S. (2001). Ordinary magic: Resilience processes in development. American Psychologist, 56(3), 227–238.

- Milligan, S. (2020). Future Proofing Students: What Schools Can Do. University of Melbourne.

- Niemiec, C. P., & Ryan, R. M. (2009). Autonomy, competence, and relatedness in the classroom. Theory and Research in Education, 7(2), 133–144.

- Norrish, J. M., Williams, P., O’Connor, M., & Robinson, J. (2013). An applied framework for positive education. International Journal of Wellbeing, 3(2), 147–161.

- OECD. (2019). OECD Future of Education and Skills 2030: Learning Compass 2030. OECD Publishing.

- OECD. (2025). Skills and the Future of Work. https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/2025/12/oecd-skills-outlook-2025_ac37c7d4.html

- Ojala, M. (2012). Hope and climate change. Environmental Education Research, 18(5), 625–642.

- Ojala, M. (2016). Facing anxiety in climate change education. Journal of Education for Sustainable Development, 10(1), 78–91.

- Pekrun, R. (2006). The control-value theory of achievement emotions. Educational Psychology Review, 18(4), 315–341.

- Pintrich, P. R. (2000). The role of goal orientation in self-regulated learning. In M. Boekaerts et al. (Eds.), Handbook of Self-Regulation (pp. 451–502). Academic Press.

- Ritchhart, R. (2015). Creating Cultures of Thinking. Jossey-Bass.

- Ritchhart, R. (2023). Cultures of Thinking In Action: 10 Mindsets to Transform Our Teaching and Students’ Learning.. Jossey-Bass.

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-Determination Theory. Guilford.

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2020). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61, 101860.

- Seligman, M. E. P. (2011). Flourish. Free Press.

- Shonkoff, J. P., & Phillips, D. A. (Eds.). (2000). From Neurons to Neighborhoods. National Academy Press.

- Suriano, R., Plebe, A., Acciai, A. and Fabio, R.A., 2025. Student interaction with ChatGPT can promote complex critical thinking skills. Learning and Instruction [Online], 95(102011), p.102011. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2024.102011.

- Tankelevitch, L., et al. (2024). The metacognitive demands and opportunities of generative AI. Proceedings of CHI 2024. ACM.

- Tarafdar, M., Tu, Q., Ragu-Nathan, B. S., & Ragu-Nathan, T. S. (2007). The impact of technostress on role stress and productivity. Journal of Management Information Systems, 24(1), 301–328.

- Taylor, S. (2025). CHAT-CCC: Activity Theory and Competency Frameworks. https://sjtylr.net/2025/08/30/chat-ccc-activity-theory-competency-frameworks/ .

- Twenge, J. M., Martin, G. N., & Spitzberg, B. H. (2018). Trends in U.S. adolescents’ media use. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 8(4), 329–345.

- UNESCO. (2021). Reimagining Our Futures Together: A New Social Contract for Education.

- UNESCO. (2025). What’s worth measuring? The future of assessment in the AI age. https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/whats-worth-measuring-future-assessment-ai-age

- Visible Learning MetaX. (n.d.). Global research database. https://www.visiblelearningmetax.com

- Wiggins, G. (2014). Authenticity in Assessment, (re-)Defined and Explained.

- World Economic Forum. (2025). The Future of Jobs Report 2025. WEF.

- Xu, H., et al. (2025). Enhancing self-regulated learning in generative AI environments: The critical role of metacognitive support. British Journal of Educational Technology.

- Yeager, D. S., & Dweck, C. S. (2012). Mindsets that promote resilience. Educational Psychologist, 47(4), 302–314.

- Zimmerman, B. J. (2000). Attaining self-regulation. In M. Boekaerts et al. (Eds.), Handbook of Self-Regulation (pp. 13–39). Academic Press.

- Zimmerman, B. J. (2002). Becoming a self-regulated learner: An overview. Theory into Practice, 41(2), 64–70.

Cite this post: Taylor, S. 2026. The TEMPERed Learner in the Age of AI. Wayfinder Learning Lab [Online]. Available from: https://sjtylr.net/2026/02/13/the-tempered-learner-in-the-age-of-ai/.

Thank-you for your comments.